Support Sestry

Even a small contribution to real journalism helps strengthen democracy. Join us, and together we will tell the world the inspiring stories of people fighting for freedom!

On this special day, our editors and authors wrote a couple of words about their work at Sestry, about their heroes, their emotions - about everything that became so important during this year of working in the media.

Joanna Mosiej-Sitek, CEO of Sestry

Our year on the frontline in the fight for truth. We are a community of women. Women journalists. Women editors. Our strength is our voice. We stand for shared European values, democracy and peace. We are the voice of all those who, like us, believe that the future lies in dialogue, tolerance and respect for human rights. These people believe in a world where we can forgive past grievances and focus our energy on building a better future. They are not divided by the words of politicians. Every day, we do everything possible to listen to and understand one another, knowing that this is the only way to fight disinformation and fake news. Our voice, our struggle, is just as vital to our security as new tanks and drones. Over the past year, we have given a platform to thousands of stories in our effort to build a better world. We understand that building a strong, multi-ethnic, and united community is a long journey, and we are only at the beginning.

Maria Gorska, Editor-in-Chief

When my colleagues at Gazeta Wyborcza and I decided to create Sestry.eu, it was the second winter of the war. My newborn daughter lay in her stroller, wearing a red onesie covered in gingerbread men, and all she knew was how to smile and reach out to her mother. Today, my little Amelia is a strong toddler, running around the park near our home in Warsaw, shouting, «Mom, catch the ball!» and laughing when I lift her into my arms. She comforts her doll when it cries.

She still does not know what Ukraine is. And that is why I am doing this media project. Not to one day tell my child about her homeland, but to ensure that she grows up in an independent, safe, and prosperous Ukraine - as a free citizen of Europe.

Tetiana Bakotska, journalist

The stories we publish in Sestry make an impact - motivating readers to take action. After my article about a refugee shelter in Olsztyn that had been closed, leaving some Ukrainian families in dire straits, five Ukrainian families reached out to say they had received help. Single mothers raising young children were given food, clothing and fully stocked backpacks for school.

Thanks to the article «Sails Save Lives» and the efforts of Piotr Paliński, hundreds of meters of sails were collected in Poland to be sewn into stretchers for wounded soldiers. On August 24th 2024, Olsztyn scout Dorota Limontas delivered the sails to Kyiv as part of a humanitarian convoy, along with medical equipment for several Kyiv hospitals, donated by the Voivodeship Adult and Children’s Hospitals in Olsztyn.

After the publication about the humble mechanic, Mr. Piotr, who in 2022 donated over 500 bicycles to Ukrainian children, the initiative gained new momentum. Once again, hundreds of children - not only in Olsztyn but in other regions of Poland as well - received bicycles as gifts. Bicycles were also sent to Ukraine for orphaned children cared for by the family of Tetiana Paliychuk, whose story we also shared.

Nataliya Zhukovska, journalist

For me, Sestry became a lifeline that supported me during a challenging moment. The full-scale war, moving to another country, adapting to a new life - this is what millions of Ukrainian women faced as they fled from the war, leaving their homes behind. I was fortunate to continue doing what I love in Poland - journalism. Even more so, I was fortunate to engage with people who, through their actions, are writing the modern history of Ukraine - volunteers, soldiers, combat medics and civil activists.

I remember each of the heroes from my stories. I could endlessly recount their lives. One might think that a journalist, after recording an interview and publishing an article, could simply move on. That is how it was for over 20 years of my work in television. The subjects of news stories were quickly forgotten. But this time, it is different. Even after my conversations with these heroes, I keep following their lives through social media. Though we have only met online, many of them have become my friends. Reflecting on the past year, I can only thank fate for the opportunity to share the stories of these incredible, strong-spirited Ukrainians with the world.

Aleksandra Klich, editor

When we began forming the Sestry editorial team a year ago, I felt that it was a special moment. Media like this are truly needed. In a world ravaged by war, overwhelmed by new technologies and crises, where information, images, and emotions bombard us from all sides, we seek order and meaning. We search for a niche that offers a sense of safety, space for deep reflection, and a place where one can simply cry. That is what Sestry is - a new kind of media, a bridge from Ukraine to the European Union.

Working with my Ukrainian colleagues has restored my faith in journalism. It has rekindled in me the belief that media should not just be click factories or arenas of conflict, but a source of knowledge, truth - however painful - and genuine emotions, which we can allow ourselves to experience in the hardest moments. Thanks to my work with Sestry and the daily focus on Ukraine, the most important questions have come alive within me: «What does patriotism mean today? What does it mean to be a European citizen? What does responsibility mean? What can I do - every day, constantly - to help save the world? And finally: Where am I from? For what purpose? Where am I headed?» These questions do not leave a person at peace when they stand on the edge. We create media in a world that is on the edge. The women of Ukraine, their experiences and struggles, remind me of this every day.

Mariya Syrchyna, editor

Over our first year, our readership has grown steadily - numbers show that our audience has increased 8-10 times compared to last year. This growth is because Sestry is no ordinary publication. Most of us journalists live in other countries due to the war, but from each of these countries, we write about what pains us the most. About Ukraine and its resilient people. About what hinders our victory over the enemy - hoping to reach those with the power to help. About the challenges we face in our new homes and how we overcome them. About our children.

We strive to talk to people who inspire and bring light in these dark times - volunteers, artists, doctors, athletes, psychologists, activists, teachers, journalists. But most importantly, we tell the stories of our warriors. I once dreamed that Ukraine’s elite would change and that the country’s fate would be shaped by worthy people. That wish has come true - though in a cruel way. The new heroes of our time are the soldiers who nobly bear the weight of the fight against both the enemy and the world’s indifference. Here, at Sestry, we tell their stories again and again to everyone who has access to the internet and a heart. In three languages. We hope that these stories will ensure their names are not forgotten and their deeds are not distorted.

A sister is someone who can be anywhere in the world but still feels close. She may annoy you, but if someone offends her, you are the first to defend her and offer a hand. That is exactly the kind of publication Sestry aspires to be - reliable and close. All the way to victory, and beyond.

Maryna Stepanenko, journalist

I have been with Sestry for nine months. In that time, I have conducted 22 powerful interviews with people I once only dreamed of speaking to in person. Politicians, generals, commanders and even the deadliest U.S. Air Force pilot. Getting in touch with him was a challenge - no online contacts, except for his publisher. There was also a fan page for Dan Hampton on Facebook. As it turns out, he manages that page himself and is quite responsive to messages.

It took me two months of persistent outreach to secure an interview with Kurt Volker, but I eventually succeeded. And my pride - Ben Hodges, whose contacts were once obtained under strict confidentiality.

In these nine months, I have learned a few key lessons: do not be afraid to ask for an interview with someone you admire, and when choosing between talking to a Ukrainian celebrity or a foreign general, always opt for the general. I am grateful to be the bridge between their expert opinions and our readers.

Kateryna Tryfonenko, journalist

«Why did you ask me that?». This is one of those funny memorable occurrences. I was working on an article about military recruitment, with part of the piece focused on international experience. One of the experts I spoke with was an American specialist from a military recruitment center. I made sure to tell him upfront that the questions would be very basic, as our readers are not familiar with the intricacies of the United States military system. He had no objections. We recorded the interview, and a few days later, I received a message from him that began, «I am still very puzzled by our conversation. I keep thinking about the questions you asked me. Why did you ask me that?». The message was long, and between the lines, it almost read «Are you a spy?». This was a first for me. To avoid causing him further distress, I offered to remove his comments from the article if our conversation had unsettled him that much. However, he did not object to the publication in the end. Although I wonder if, to this day, he still thinks it was not all just a coincidence.

Nataliya Ryaba, editor

I am free. These three words perfectly describe my work at Sestry. I am free to do what I love and what I do best. Free from restrictions: our editorial team is a collective of like-minded individuals where everyone trusts each other, and no one forbids experimenting, trying new things, learning, and bringing those ideas to life. I am free from stereotypes. Our multinational team has shown that nationality and historical disputes between our peoples do not matter - we are united, working toward the common goal of Ukraine’s victory and the victory of the democratic world. I am free to be who I want to be in our newsroom. Yes, I work as an editor, but I can grab my camera and run as a reporter to protests or polling stations - wherever I want to go. No one forbids me from creating what I want, and I am grateful for this freedom. It gives me wings.

Anastasiya Kanarska, journalist

Like many women, I always thought I wanted to have a son. Well, maybe two kids, but one of them had to be a boy. But as my understanding of myself and the world grew, and the likelihood of not having children at all increased, the idea of being a good mother to a happy, self-sufficient daughter became an exciting challenge. Learning from each other, respecting personal boundaries, and caring for one another - that is what makes working in a women’s circle so empowering. For me, starting work with Sestry coincided with a deeper exploration of my female lineage - strong women like my colleagues, who at times embody Demeter, Persephone, Hera, Aphrodite, Artemis, or Hestia. The themes of my articles, whether written, edited, or translated by me, often mirror my own life events or thoughts. Maybe that is the magic of the sisterhood circle.

Olena Klepa, SMM specialist

«I feel needed here». I went to my first interview with Sestry three months before the official launch of the project: in old DIY shorts, a T-shirt from a humanitarian aid center, with a «dandelion» hairstyle and seven years of TV experience. I was not looking for a job. I was content working as a security guard at a construction site, always learning, taking free online training. But for some reason, all my supervisors kept asking: «Have you found something for yourself yet? Any interesting opportunities?» They would tell me I did not belong there and was meant for something greater.

Sestry found me. So, when I first went to the meeting, I decided, «All or nothing». It was not a typical interview. It was a meeting of people with similar values and a shared goal. We spoke different languages but understood each other instantly. The plans were ambitious and, at first glance, unrealistic. They needed a social media manager. The responsibility scared me, but I never say «I can't» until I try. Experience has shown that you can learn anything. At Sestry, I feel needed. I feel like I have room to grow. I love that I can combine all my accumulated experience here, that I can experiment. But most importantly, I no longer feel guilty. My country is at war. The enemy is not only on the frontlines. Russian propaganda has extended its tentacles far beyond its borders. By creating social media content, telling stories about Ukrainians on the frontlines to people in Poland, and showing Ukrainians that Poles «have not grown tired of the war», I am helping Ukraine hold its ground in the information space.

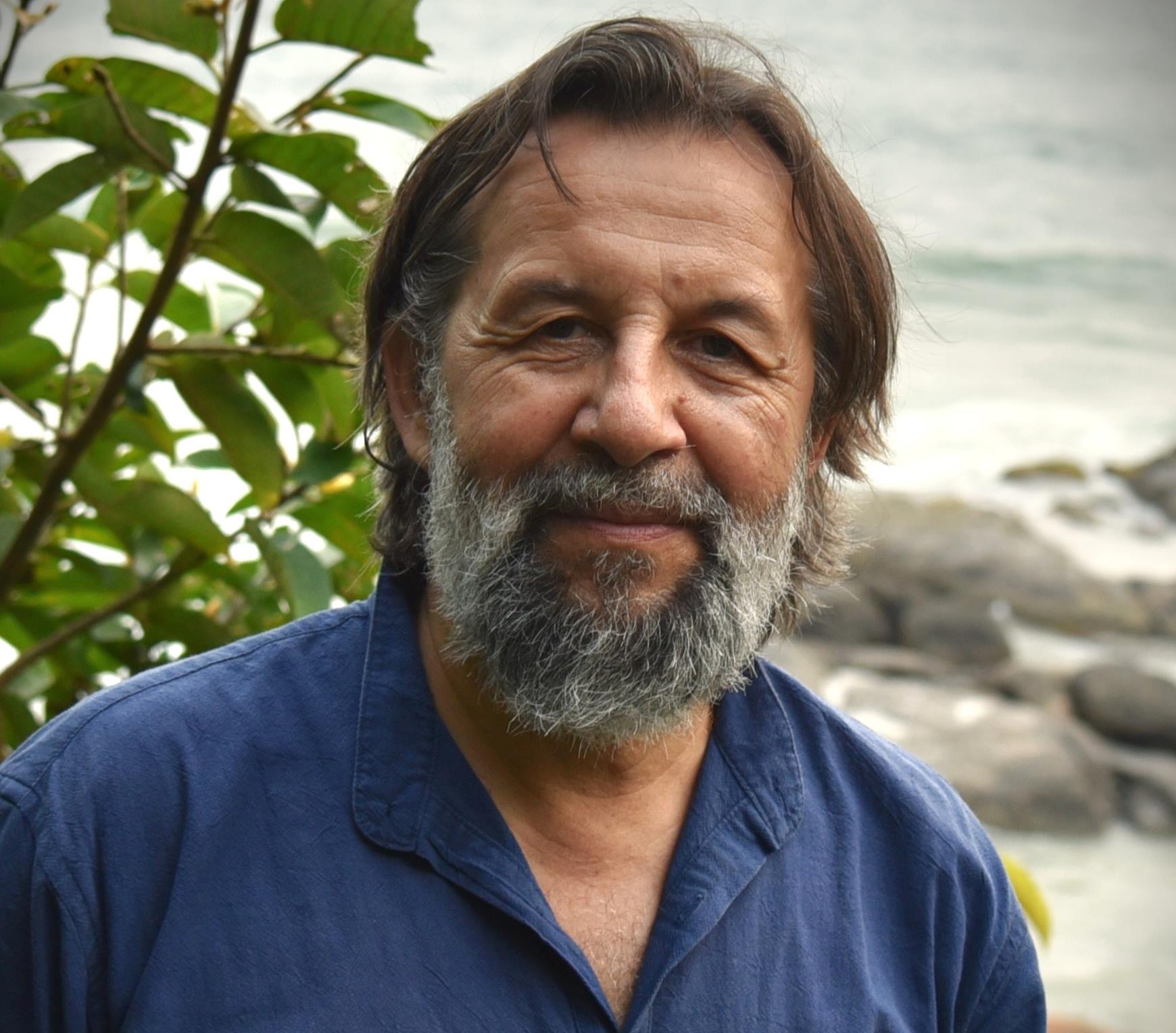

Beata Łyżwa-Sokół, photo editor

Many years ago, a photo editor colleague considered changing jobs and trying her luck abroad. However, one editor strongly advised her against it: «You will never be as recognised in a newsroom in New York or London as you are at home. You will never reach the same level of language proficiency as your native-speaking colleagues. At best, you will be an assistant to the head photo editor. In a foreign newsroom, you will always be a foreigner». She listened and stayed in the country, despite having studied English at university and being fluent enough that language would not have been a barrier. A few years later, she left the profession altogether, deciding that journalism no longer had a place for her - that it simply did not exist anymore.

Since then, the media landscape has changed drastically. Many believe that in the age of social media, journalism is no longer necessary. The world is evolving, and so are the media. However, I never stopped believing in its importance. I did not run away from journalism; instead, I sought a new place for myself. That is how I found Sestry, where I met editors and journalists who had come to Poland from war-torn Ukraine. After a year of working together, I know that we are very similar in many ways, but also differ in others. We listen to each other, argue, go to exhibitions together, and share a bottle of wine from time to time.

When I started working at Sestry, and we were discussing what kind of photographs should illustrate the site with our editor-in-chief, Mariya Gorska, I heard her say, «This is your garden». It was one of many fantastic phrases I heard during the months of working together - words that shaped our professional and personal relationships. In an era of fake news, bots and media crises, it was particularly important to me, as the photo editor of Sestry, to consider how we tell the story of what is happening in Ukraine through photography. I observe the media around the world, and thanks to the editors on our site, I notice that these images are often superficial, not based on direct testimony or experience, and rely on stereotypes.

For me, direct contact with Ukrainian journalists and editors is invaluable in my daily work. I am convinced that journalism projects based on such collaboration represent an opportunity for the media of the future. They are a guarantee of reliability and effectiveness in places where people’s lives are at stake, even in the most remote corners of the world.

In Kathryn Bigelow’s film «Zero Dark Thirty», there is a scene where the protagonist, a CIA agent responsible for capturing Osama bin Laden, faces a group of Navy SEALs participating in the operation. One of them, sceptical about the success of the mission (particularly because it is being led by a woman), asks his colleagues: «Why do you trust her? Why should I trust her?». Another replies: «Because she knows what she is doing». That is exactly how I feel working at Sestry. I work with editors and journalists from Ukraine who know what they are doing and why - and I feel incredibly comfortable because of that.