Support Sestry

Even a small contribution to real journalism helps strengthen democracy. Join us, and together we will tell the world the inspiring stories of people fighting for freedom!

Croatians have warmly welcomed Ukrainians since the very first days of the full-scale war. According to official data, the country has taken in approximately 30 thousand Ukrainian refugees. Stress, language barriers, and lack of employment are just some of the challenges faced in a new country. In July 2022, several proactive Ukrainian women, who had overcome the tough path of adaptation themselves, decided to unite for a good cause. They established an organisation for their fellow countrymen called «Svoja», which has been actively helping those in need for three years now.

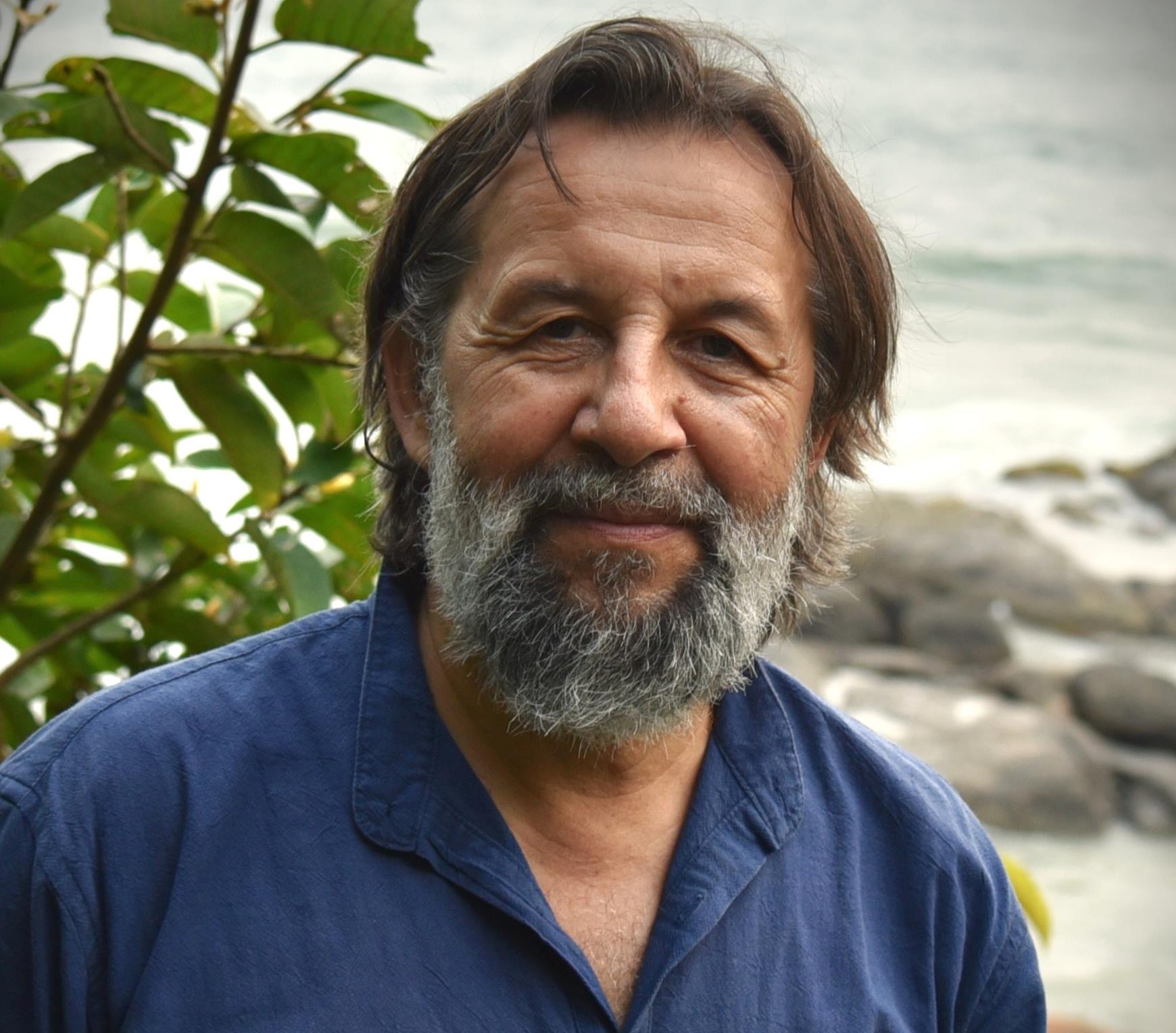

Iryna Pronenko: «I could not comprehend that war could happen twice in my life»

I come from Luhansk. I studied there, graduated from the Faculty of Psychology, and managed to work in my profession before 2014. As soon as the war began, my future husband and I left the city. We never wanted to live under Russian rule. In Luhansk, we left two apartments and all our belongings behind, embarking on a new life in Kharkiv. We invested our earnings in professional development and education because the situation in 2014 demonstrated that those with knowledge and experience had a better chance of finding employment. It took us eight years to build a new life and make something out of ourselves. By the time of the full-scale war, I was a managing partner of an HR consulting agency, and my husband had a psychological counselling practice. However, like in 2014, the war caught up with us again. In mid-March 2022, we decided to leave. Due to my husband’s disability, we both went abroad.

We chose Montenegro, not knowing that fate would decide otherwise. Our route passed through Hungary and Serbia. However, when boarding a bus to Belgrade, the driver refused to let us on with our cat. We started looking for another way to get to Montenegro, and it led us through Zagreb. At that point, we had been on the road for five days.

We arrived in Zagreb on 17 March 2022. Perhaps due to exhaustion and the sense of peace, we decided to stay there.

On Facebook, I found a group helping Ukrainians in Croatia. I wrote that a couple with a cat was looking for accommodation. That same day, we received a reply: «We would be happy to host you»

Within a few days, I saw a social media announcement about free Croatian language courses. Over the next month and a half, I studied. Finding a job in Croatia was not easy, but I continued working remotely in Ukraine. Eventually, I met the head of the «Svoja» organisation, offered my help, and got involved in volunteering.

I still help Ukrainians in Croatia with career counselling, setting up businesses, and job searches - such as writing CVs and preparing for interviews. Before us, no one else was doing this. With my beginner-level Croatian, I accompanied people to interviews. Later, when the association won a grant and began receiving funding, I was employed there as a specialist in employment and career consulting.

When the full-scale invasion began, I could not comprehend that war could happen twice in my life. There was an inner protest when you think, how many times must I start over?

In Croatia, it so happened that we created our own job. Its results are evident. Over two years, we have employed more than 500 people. For now, I do not plan to return to Ukraine - and I have nowhere to return to.

Tetyana Chernyshova: «It is very important to feel that you are not alone»

We are from Kyiv and, like many others, thought that the war would not last long - at most, three days. I remember sitting in the bomb shelter with my children. We have three. At that time, one daughter was eight years old, the other six. Our eldest was no longer living with us.

On the second day of the full-scale war, my husband said: «We are leaving. You have half an hour to pack. Whatever you take is yours. We are heading to Western Ukraine». We had a huge argument because I thought it was inappropriate and unnecessary to leave home. I took documents, money, some belongings, and underwear for three days. For some reason, I was convinced that we would return within a week.

On the way, along the Zhytomyr highway, we saw a lot of military equipment. Missiles were being shot down overhead. The children asked: «Why are there fireworks during the day? You cannot even see them». From Kyiv to Zhytomyr, it took us about seven hours. The next day, we heard horrifying news that cars were burning on the Zhytomyr highway and that there were Russian tanks there. We reached the Slovakian border. We managed to find a place to stay in a student dormitory. A few days later, we decided to go abroad with the children. Friends invited us to Zagreb, Croatia. My husband stayed behind, and I went with the children to the pedestrian border crossing. In a queue over seven kilometres long, we stood for 12 hours.

After crossing the border, I panicked. My mind was in chaos. I called the woman who had invited us to Croatia. She fully coordinated us. The next day, we travelled by train to Budapest and from there to Zagreb. And again, we thought we would stay for a week at most - and then return home. However, on March 8th, our house near Kyiv was destroyed by an enemy projectile. It was a direct hit. All that was left of the house was a pile of rubble. That was the moment I understood the gravity of the situation. At first, I was like an animal trapped in a cage. Only later did I start going outside, exploring where the shops and hospitals were.

The children were very well received at the local school. Simultaneously, they studied online in Ukraine. One daughter immediately integrated into the group, while the other struggled. She cried every day and said: «Mum, I do not want to go to school. I do not understand what they are saying. They hug me, and I do not want to hug them».

Croatians are a kind and empathetic nation. They sympathised with us greatly because 30 years ago, they also experienced war and understand what it is like. I worked online as a lecturer in therapeutic physical education at Shevchenko University. However, we were eventually told that it was impossible to conduct lessons from abroad. I had to resign. Until I learned the Croatian language, I worked wherever I could - cleaning floors and toilets, babysitting. In March 2022, I accidentally met a Ukrainian woman named Nataliya, and later, we founded our association «Svoja». We decided to provide informational support to Ukrainians who found themselves displaced by the war.

When you are in a foreign country and do not know your rights, anything can happen. For example, there were cases where people were deceived about their wages at work

Today, I work as a waitress in a café near my home and my children’s school, and I volunteer at «Svoja». From my own experience, I know that people arriving in a new place often do not know where to start or how to proceed. As for my adaptation, I have learned the language and gained some understanding of how to survive here. However, I still feel like a stranger in a foreign country.

Nataliya Hryshchenko, Head of the Ukrainian Association in Croatia: «For us, «Svoja» is one of our own»

We established «Svoja» in July 2022. At that time, it was not easy for anyone who had found temporary refuge in Croatia. We lived without unpacking our suitcases, waiting to return home the next day. Unfortunately, that did not happen. So, we decided to create our own community called «Svoja». To gain people’s trust, it was necessary to officially register the organisation. We were fortunate to meet the «Solidarna» Foundation, which supported us both legally and financially. They provided us with our first grant, registered a fund to support Ukrainians, and acted as our mentors.

Today, our core team consists of four people brought together by chance. Each of us has our own area of focus. We managed to build a community of Ukrainians who use our services, comprising over three and a half thousand people.

It is very important to feel that you are not alone. By helping others, we help ourselves cope with the pain that the war inflicts on all of us

First and foremost, we provide informational support. Our main focus areas are employment and education. We collaborate with the local employment fund. We have a database of people who contact us and respond to their requests quickly. There is no bureaucracy with us. We work with over 70 employers who provide us with job openings. We also cooperate with legal firms that support refugees. Additionally, we assist Ukrainians in validating their diplomas. The number of people seeking our services grows every year. People want to work in their professions and receive fair pay.

We also work in the field of human rights protection. We collaborate with the Ombudsman of the Republic of Croatia and have even had to seek their assistance. For example, 20 kilometres from Zagreb, there is a settlement of Ukrainians where there was no family doctor after the previous one resigned. This is a significant issue for Croatia, which lacks two thousand doctors. We wrote a collective appeal to the Ombudsman, who addressed the issue through the Ministry of Health.

Additionally, we organise language courses. So far, over 200 people have completed our programmes. From January 2025, we plan to introduce a Croatian language course specifically for medical professionals. We have also established an IT community that offers training sessions. Currently, we are running a course on artificial intelligence. Moreover, we provide regular psychological support lectures.

There are requests for psychological, physical, and even material support. Recently, we collected items and food for people who had just arrived from Ukraine. Their numbers continue to grow. Last year, according to official data, there were 22,900 Ukrainians in Croatia; by 2024, this number had risen to over 27 thousand.

Finding us is simple - we have our own website and are also active on Facebook, Telegram and YouTube.

A TV host, journalist and author of over three thousand materials on various subjects, including some remarkable journalist investigations that led to changes in local governments. She also writes about tourism, science and health. She got into journalism by accident over 20 years ago. She led her personal projects on the UTR TV channel, worked as a reporter for the news service and at the ICTV channel for over 12 years. While working she visited over 50 countries. Has exceptional skills in storytelling and data analysis. Worked as a lecturer at the NAU’s International Journalism faculty. She is enrolled in the «International Journalism» postgraduate study program: she is working on a dissertation covering the work of Polish mass media during the Russian-Ukrainian war.