Support Sestry

Even a small contribution to real journalism helps strengthen democracy. Join us, and together we will tell the world the inspiring stories of people fighting for freedom!

Війна розвинула в нас навички, які ми б ніколи не хотіли мати. Наприклад, блокувати емоції та жити з горем. Цей шлях щодня проходять тисячі жінок, які чекають своїх близьких з полону. Невизначена втрата — турбулентне відчуття, коли живеш з безкінечним потоком відчаю й питань: що зараз відбувається з рідною людиною, де вона взагалі, як переживе ніч, поки ти засинаєш у своєму ліжку, чи побачитеся ви знову, та як допомогти їй і… собі?

Про невідомість складно говорити

Жінка, яка переживає невизначену втрату, прокидається дуже рано, до дзвінка будильника, й відразу перевіряє соціальні мережі й групи зниклих безвісти. З моменту, коли вона почула страшні слова: «Ваш син зник безвісти», «Ваш чоловік потрапив у полон», — вона шукає будь-яку інформацію, готова зробити будь-що, аби дізнатися бодай щось про рідну людину.

«Невизначена втрата не має меж, — розповідає Анна Грубая, кураторка проєкту GIDNA, що надає психологічну допомогу жінкам, які переживають втрату. — Це невідомість, і тому складно про це говорити. Інколи зрозуміліше говорити про фактичну втрату. Боляче, але зрозуміліше. Саме невизначеність є тією травмою, яка руйнує людину зсередини щодня — роками.

Жінка відчуває втому, яка накриває дедалі сильніше. Вона злиться, що її надія гасне, злиться на весь світ. Вона відмовляє собі в усьому, забороняє собі радіти звичним речам, блокує всі емоції і живе лише краплею надії, що рідна людина повернеться».

Три місяці тому до програми проєкту GIDNA (напрям «Невизначена втрата») долучилася Ірина Козарєва, яка вже три роки чекає на сина з російської неволі. Для жінки це три роки без сну, і два — без жодної звістки від Ярослава, оборонця Маріуполя, який потрапив у полон у травні 2022 року. Саме тоді вони спілкувалися востаннє.

«Синку, у тебе є план Б?»

Ірина — мати шести прийомних синів. І кожен — як окремий всесвіт, зі своїм характером і палким бажанням боротися за своє. Ірина з усмішкою згадує, як всі шестеро прагнули піти з нею на Майдан під час Революції гідності:

— Вони шарфами обмотали обличчя, одягли каски, наколінники, налокітники, взяли біти й кажуть: «Підемо з тобою. Якщо ми не йдемо — то й ти не йдеш».

А потім почалася війна. Ярослав, оборонець Маріуполя, тоді був футбольним фанатом, вболівав за ФК «Динамо». Мати згадує, що вони разом з товаришами завжди мали активну громадянську позицію, брали участь в акціях, разом доєдналися до «Азову».

Ярослав до останнього не хотів зізнаватися матері, що став на захист країни. Але поділився таємницею зі старшим братом, а той не витримав і розповів усе мамі. Плакати вже не було сенсу, згадує Ірина: «Я просто запитала його: “Чим я можу тобі там допомогти?”».

Коли почалося повномасштабне вторгнення, Ярослав був першим, хто зателефонував. — Вже ввечері я писала йому: «Синку, ви будете в повному оточенні, у вас є план Б?». А він казав: «У нас є всі плани, ми озброєні й знаємо, що робимо». Далі — лише листування.

В якийсь момент Ярослав зник, перестав відповідати. Ірина почала рахувати дні…

Новини про сина до Ірини прийшли раптово — від його дівчини, з якою жінка ще не була знайома. На той момент це було вже 20 днів страшної тиші. Як з’ясувалося, Ярослав був поранений. Під час боїв за Маріуполь отримав складну контузію, втратив слух, зір і координацію рухів. Пізніше на шпиталь, в якому лікувався Ярослав, російська армія скинула бомбу. Хлопця доправили на «Азовсталь». На 21-й день він написав матері, що живий і просто не було зв’язку.

— Я кажу: «Знаю, як у тебе все добре, мені вже розповіли». Він так і не оклигав, на кожен приліт у нього була блювота. Щоб воювати, треба ж бігати, лазити, ховатися, повзти. Він усього цього вже не міг.

— Я писала синові, що їх тут називають спартанцями. А він голосове мені записав уночі: «Якщо мені не зраджує память, всі вони загинули. А я не хотів би тут сконати, в мене ще навіть сина немає»

Все в нього з гумором, все легко. Він намагався мене не травмувати й максимально все приховував, — розповідає Ірина.

Востаннє Ірина говорила з сином 18 травня 2022 року, коли той вимушено здався у полон. Перед виходом захисники отримали наказ знищити телефони й зброю, тож зв’язок із сином зник.

Ірина згадує, як уважно стежила за новинами, як просила сина під час тієї останньої розмови говорити все, що накаже ворог, аби лише його не катували, як розглядала в групах кожну фотографію й кожне відео, шукаючи Ярослава.

«Я вила, кричала й торгувалася з Богом»

Разом з іншими полоненими з «Азовсталі» Ярослава доправили в Оленівську колонію. Зв’язок був заборонений, але комусь з бранців пощастило дістати sim-карту, і Ярослав зателефонував своїй коханій Валерії. Розмова тривала 1 хвилину. А далі була страшна звістка — росіяни влаштували теракт на території колонії. Загинуло щонайменше 53 українських захисники, понад 130 було поранено. У бараці, який підірвали, було 193 людини, зокрема Ярослав.

— Я чекала дзвінка, і тут дізнаюся про теракт. Валерія (дівчина Ярослава — Авт.) мені повідомила й відразу розридалась: «Я знаю, він там». Ми з нею плакали разом. За всіх наших людей. А на наступний день вже були списки. Мені надіслали частину списку, і Ярик у ньому був. Я знала, що він не може загинути, бо я молилася день і ніч. Я без перестанку вила, кричала й торгувалася з Богом. Просила: «Боже, забери мене, тільки нехай він живе!».

Коли Ірина отримала повний список і побачила заголовок, виявилося, що це був список поранених, а не загиблих. За кілька днів Ірині подзвонила санітарка зі шпиталю й повідомила, що Ярослав живий, у нього все добре, тільки одна рука не працює. Ярославу вдалося зв’язатися з близькими зі шпиталю лише раз, Ірина пригадує, що голос сина був такий, наче він дуже тяжко поранений. Тоді він просто сказав, що живий, спитав, як усі. І це була їхня остання розмова.

Після полону жінка побачила сина на одному з пропагандистських телеграм-каналів у репортажі про те, як окупанти «піклуються в ДНР про нацистів».

— Він нічого не говорив. Сидів упівоберта. Мені зробили скрін з відео. Я побачила, що Ярослав дуже схуд, кілограмів на 20. Раніше був такий міцний, накачаний, займався спортом. Він готувався, щоб бути сильним, бути вправним у військовій справі. Він так цим пишався. Отак побачила його профіль — і все... З тих пір два роки — повна тиша.

Ірина зізнається, що чекала будь-якої звістки від сина, вважала, що якщо його побачить — їй стане легше. Проте насправді біль лише посилився: «Я ридала й ридала, ридала й ридала… Тільки очі закриваю — бачу вибух, пожежу, як вони в цій пожежі, як люди горять, я навіть відчувала запах плоті й крові. Ніби сама там була.

Зрештою Ірина звернулася за допомогою. Психіатр встановив діагноз — ПТСР. Ірині призначили ліки, щоб вона знову могла спати. Проте найбільше допомагали не вони, а людська підтримка й спілкування:

— Мій колега якось подивися на фото сина й сказав: «А чому ти взагалі плачеш? Рука є? Є! То подякуй Богу. Кістки є, мясо наросте». І ви знаєте, мені отак раз — і стало легше. Інколи таке просте слово знімає пелену з очей.

Ірина не мала жодних новин про сина аж до обміну, який відбувся на Великдень, 19 квітня. Один зі звільнених військовополонених розповів, що чув про Ярослава. Навіть не бачив — лише чув.

— Дівчина Ярослава, Валерія, знайшла цього чоловіка в соцмережах. Він сказав, де знаходиться Ярослав, а також те, що він здоровий. Він його не бачив, але чув постійно, бо був у сусідній камері. Сказав, що він тримається і моральний стан хороший. Але не знаю, наскільки цьому можна вірити, адже вони всі хочуть нас заспокоїти.

«Відчувала себе надщербленим глечиком, з якого все виливається»

Два роки Ірина жила у невідомості, як тисячі сімей по всій Україні. Проте людський ресурс не безкінечний. Жінка стала відчувати, що ліки вже не допомагають, сон знову зник. Зізналася, що якби не собака, вона б і не вставала з ліжка.

— Все втратило сенс. І раптом я побачила в телеграмі, в якомусь з чатів оголошення про проєкт GIDNA. Мене ніби щось торкнуло. Але подумала, що є люди, яким важче, ніж мені, і вирішила нікого не турбувати. Проте за декілька днів повернулася, знайшла те оголошення і заповнила анкету. Мені відразу зателефонували й дуже тепло зі мною поговорили.

Ірина ділиться, що біль і горе відчуваються ще дужче, коли не маєш з ким їх розділити:

— Всі втомилися. Навіть мої старші діти й подруги вже не можуть говорити про це зі мною. Вони не можуть — і я мовчу. Але це важко, бо біль нікуди не зникає.

Щире спілкування й підтримка — неймовірна допомога для людини, яка переживає горювання, впевнена Анна Грубая, психологиня та кураторка проєкту GIDNA:

— Фрази на кшталт: «Тримайся», «Все буде добре», «Може, вже час відпустити» викликають гнів і злість, адже ніхто не знає, як буде і як важко триматися. Натомість краще запитати: «Як я можу тобі допомогти?»

Людина сама відповість, бо для когось — це просто посидіти помовчати, для когось — подивитися фото й поринути у спогади, ще для когось — поговорити про те, як важко.

Ірині вдалося зустріти своїх людей у проєкті GIDNA:

— Знайшлися люди, які хочуть говорити. Так, це їхня робота. Але ці люди небайдужі. Я вже третій місяць в терапії і відчуваю суттєві зміни.

Сьогодні жінок і матерів, які чекають на своїх близьких з полону, Ірина має щиру пораду:

— Впевнена, що якби я розповіла Ярику, як сама себе карала і яке жахливе почуття провини в мене було щодо того, що я отак просто його відпустила, — йому б це дуже боліло. Він би хотів, щоб я жила, жила на повну. І Роберт (молодший брат Ярослава, який доєднався до ЗСУ) теж постійно каже, що треба жити.

Радіти кожному листочку, кожній квіточці, вітру, дощу. Вони там цього всього позбавлені. А вони ж пішли туди, щоб ми жили

Ірина ділиться, що вже після другої зустрічі з психологом відчула, що в ній все ще є сила:

— Коли я прийшла в терапію, то відчувала себе якимось надщербленим глечиком. У тріщинах, з дірками. З якого все виливається, скільки туди не налий, і я вже нічого в собі не утримувала. Ми стали працювали над цим. Аж поки я не відчула, що ще можу послужити. Важливо навчитися не заштовхувати біль глибоко всередину, де йому не місце, а шукати професійної допомоги.

Робота з терапевтом — це поступовий шлях для відновлення відчуття безпеки та стабільності, навіть коли переживаєш горе. Часто без неї неможливо повернутися до повноцінного життя.

— Спочатку виникає спротив — жінка не хоче продовжувати терапію, і це нормальна реакція, — пояснює Анна Грубая. — Адже терапія — це зустріч зі своїми емоціями і почуттями, це спогади. І якщо після фази спротиву жінка все ж знаходить сили продовжити — це гарний знак. Згодом вона починає довіряти психотерапевту, формується хороший контакт — і це другий гарний знак. З'являється турбота й піклування про себе у стані невизначеності — третій гарний і вагомий крок, який допомагає формувати нові копінг-стратегії, як жити у невизначеності й не руйнувати себе.

Ірина досі в терапії, мріє про повернення сина. Переймається, щоб від радості зустрічі не втратити свідомість: «Я знаю, що не можна на них нападати з обіймами. Що краще першою не торкатися. Багато знаю, багато читала щодо їхньої травми. Але я хочу бути біля нього. Неважливо, які в нього діагнози».

Жінка планує на першій зустрічі подарувати Ярославові Lego, яке колись в дитинстві подарувала, а потім забрала на емоціях, бо діти бешкетували й не слухалися:

— На той час я не усвідомлювала, що для дітей це найцінніша валюта. А потім, коли син був там, на «Азовсталі», я попросила в нього за це вибачення. А він сказав: «Ти що. Ти найкраща мама, яка тільки могла б у мене бути!»…

<frame>Проєкт GIDNA фонду Future for Ukraine допомогає жінкам, які постраждали від наслідків жорстокої війни Росії проти України, повернути емоційну рівновагу. У травні виповнюється рік, відколи у межах проєкту працює спеціальна програма роботи з невизначеною втратою. Психологи проєкту надають безкоштовну підтримку жінкам, чиї рідні зникли безвісти на війні або перебувають у полоні. Кожна учасниця програми отримує 16 консультацій з психологом, а також щомісячну підтримку після курсу. За рік роботи команда Невизначеної втрати отримала 41 звернення, 35 жінок вже завершили терапію і навчилися екологічно проживати свій біль. А ще — знову почали жити з надією в серці.<frame>

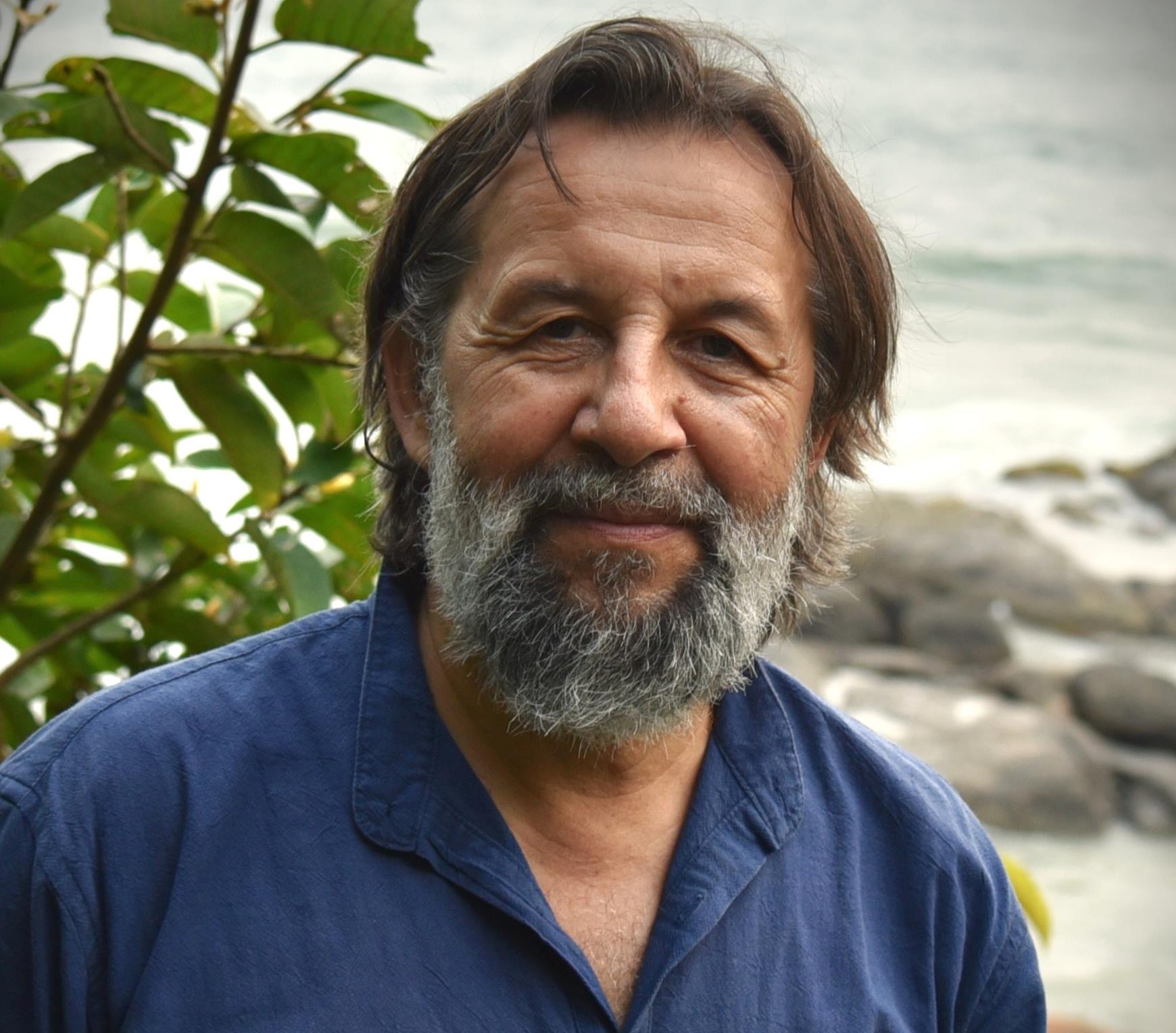

Ukrainian journalist, editor, TV host and author of analytical programs. She developed her media career in Ukraine. Since 2021, after getting married, she has been living in the Podkarpackie Voivodeship in Poland. She lived and worked in Lviv at the newspaper «Progress», and on the TV channels of the Lviv State Broadcaster, NTA, 5 Channel, and Espresso. She was the author of analytical materials and journalist investigations programs. She hosted the analytical program «Information Evening-Lviv» on 5 Channel. She is an honourable graduate of the Ivan Franko National University of Lviv with a master’s degree in journalism and studied in Rome, Italy, at the Dante Institute’s language school. After moving to Poland, she continues to engage in journalism. Her life motto is: Be useful to Ukraine wherever you are. Do well what you know how to do! Love life and people.